1. Direct pleasure

Aesthetic pleasure is the first universal hallmark of the work of art, says Dutton. This may well be a concept which is out of date in the twenty first century, as it does not allow for the challenging, or that which is designed to shock, both of which are aspects of art today. However, that aside, I am considering the first characteristic on Dutton’s list.

![VermeerR]](https://carmenmills54.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/vermeerr.jpg?w=775)

“The art object … is valued as a source of immediate experiential pleasure in itself, and not essentially for its utility in producing something else that is either useful or pleasurable.”

In relation to fine art, this is the characteristic that immediately comes to mind. As we look at a piece of art, we experience pleasure. This may include work which is deemed to be ugly or offensive, as well as the beautiful. It may be because of the colours employed, or the forms, or the materials used, or a complex combination of many factors.

My own examples of work giving direct pleasure range from a still life by Morandi and Leonardo’s The Virgin on the Rocks; to a nude in the Cubist style by Picasso and The Ocean Park series by Diebenkorn. Well, really the list is endless. This is why we get drawn into art to start with, either as viewers or makers, because we experience pleasure as a direct result of looking at the art object.

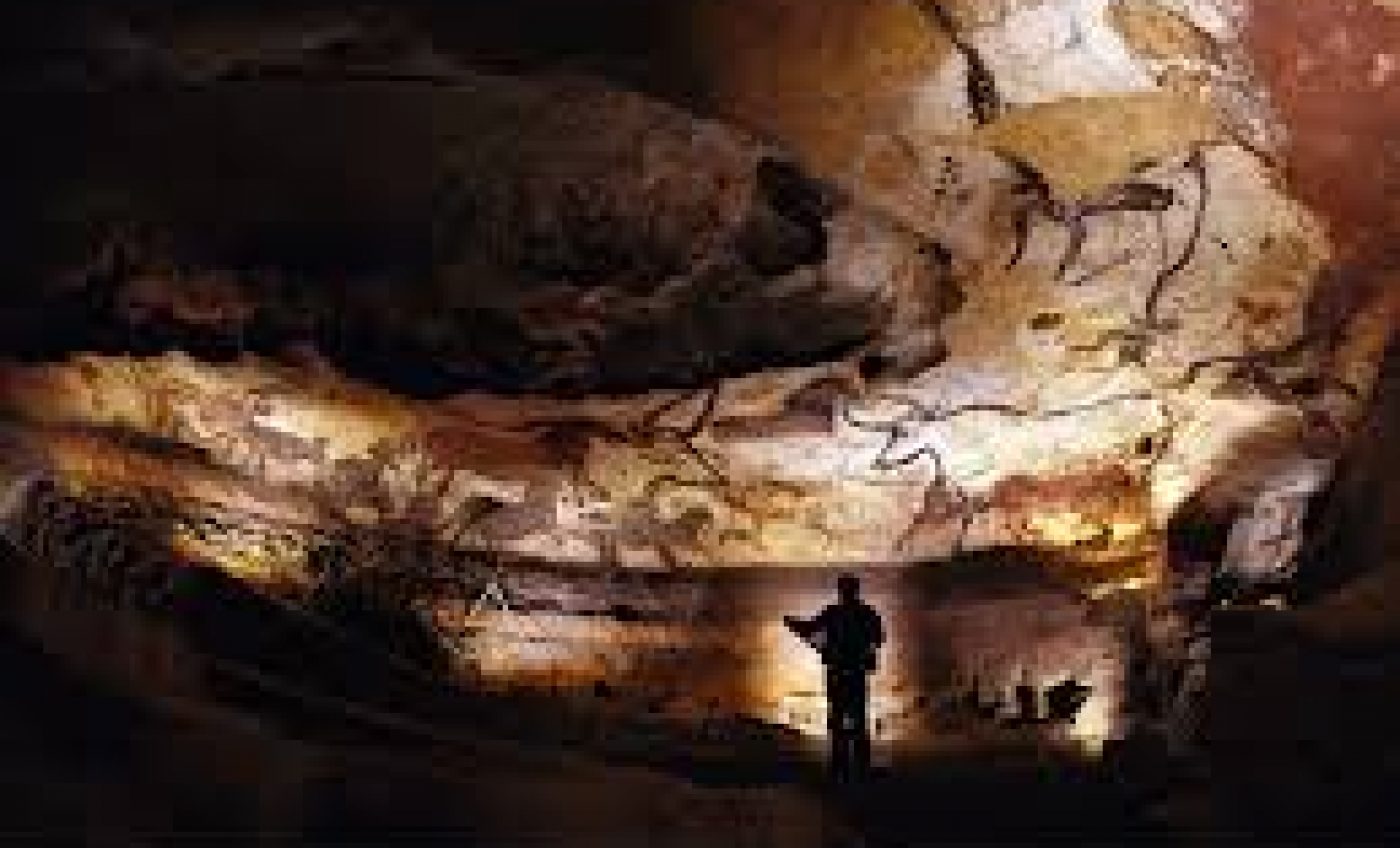

Where does this pleasure come from? It seems to be inbuilt. Archaeology supports the idea that humans have always appreciated decoration and pattern, all the extra visual marks that have no particular practical function but which add to the enjoyment of the whole. So the most ancient of pottery has marks on it which have no practical reason for being there, but which indicate a capacity for aesthetic appreciation by the makers and viewers of it.

Having said that, there are occasions when the outwardly beautiful or engaging is not enough. Here I am thinking about the situation Dutton goes on to describe in some detail with regard to forgery. If it were merely an aesthetic reception of colour, line, form, texture etc, then there would be equal pleasure taken in those pieces of art which are merely copies of originals. But that is not the case. We may still appreciate something of the work, but our overall perception is tarnished by the knowledge that it is not original. This is a very interesting reaction. We seem to need truth to be a part of the whole. Where it is not truth, in other words a genuine response of the artist to the world around them seen from their own particular personal angle, we feel as if we have been manipulated to esteem something which lacks integrity, we feel cheated.

This seems to indicate that there is more than visual pleasure involved.

![ingrid-calame_33cd1642[1]](https://carmenmills54.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/ingrid-calame_33cd164211.jpg?w=775)

Perhaps this goes towards explaining why some images are valued on a popular level, but carry no credibility, earn no brownie points, with those who are more knowledgeable about art. For example, the work of artists such as Jack Vettriano. There is an appeal of form and colour which the man in the street responds to, but which carries no weight with art practitioners. In this situation, how much is a genuine response to what is before the eyes, and how much is affected by knowledge of art history, or knowledge of the working practices of the artist, or any other form of knowledge?

Which brings up the vexed question which all practising artists have to consider, that of making work that genuinely pushes practice on, and making work to sell. The gap in perception between those who know about art and those who don’t inevitably means that artists feel that what may appeal to one group may not appeal to the other, and when it comes to keeping body and soul together through the practice of art, this is a really important issue. Making work to sell may help domestic finances, but does nothing for the reputation for that artist among other artists and art establishments. Should this be redressed? After all, even artists can’t live on fresh air, and while the state takes no part in supporting those who work directly in cultural activities, they have no choice but to use their talents for commercial ends. Would some of the American Abstract Expressionist painters have found fame and fortune if they had not been paid by the government to pursue their work? And if supporting artists can be done at all, why not make it a continuing practice?

![11-cubism_Picasso_Woman-Playing-Mandolin[1]](https://carmenmills54.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/11-cubism_picasso_woman-playing-mandolin1.jpg?w=775)

![Scully_at_Atelier[1]](https://carmenmills54.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/scully_at_atelier1.jpg?w=775)